Russia is not the aggressor here

Putting all the blame on Putin for the crisis in Ukraine obscures the West's own role.

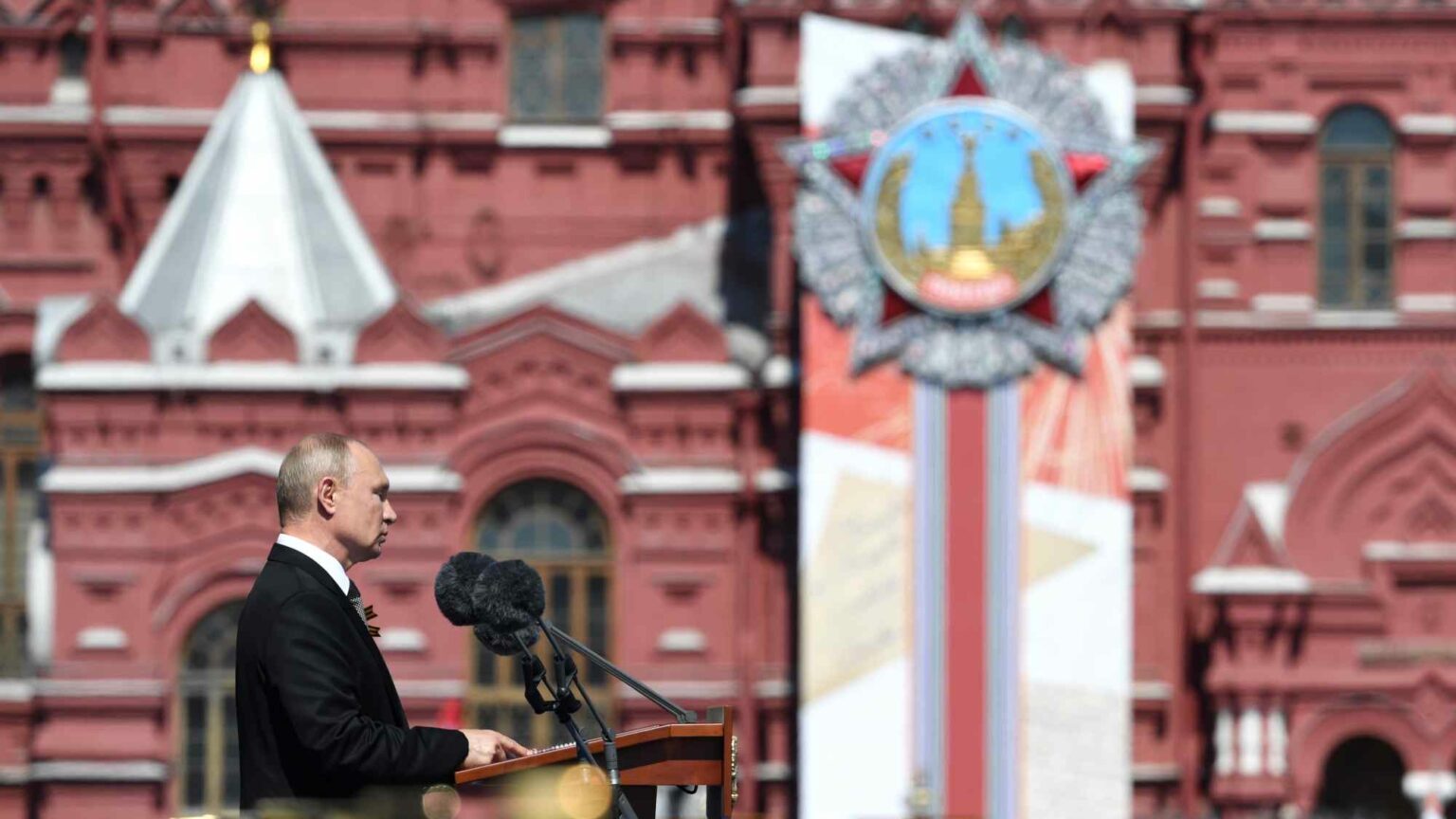

The New Statesman’s cover from last week captured the Western media’s view of Russia perfectly. Vladimir Putin, his shifty eyes impossibly close together, is pictured holding the world in one hand, while exerting a destructive force over it with the other. The headline accompanying the image says it all: ‘The Agent of Chaos.’

This is how many in Western media and political circles routinely portray Putin’s Russia – as an evil demiurge, trying to shape the world according to its own nefarious ends. That’s why, over the past year, we’ve been repeatedly told that Russia is preparing to invade Ukraine. Why we were told it had marshalled 100,000 troops on the Russian-Ukraine border in April. And why we’re told it has marshalled 175,000 troops there today. Because Putin’s Russia is a malevolent force, an agent of chaos and war, an expansionist, aggressive power willing to act with impunity.

The Sunday Times certainly thinks so. It ran a frontpage last weekend featuring the assertive headline, ‘Of course the Russians are coming to Ukraine. They want to rebuild their empire.’ The Observer’s leader this weekend was penned in a similar vein, explaining Russia’s intentions towards its neighbour as a product of Putin’s imperial nostalgia. ‘He yearns for the days when the Soviet Union was a great power’, it read, before claiming Putin had never reconciled himself to the loss of the Soviet Union: ‘This is especially true of Ukraine.’ Likewise, the New York Times claimed that ‘Putin and his close associates’ have ‘a singular fixation’ on Ukraine and other former Soviet Republics, the loss of which they see as an ‘historical injustice to be set right’.

Western politicians share in this vision. In their eyes, Russia appears as an irrational, permanently aggressive force, interfering in elections here and intervening in warzones there. And now it is set on invading Ukraine because… well… that’s just what Russia is like. It is fuelled by 19th-century dreams of imperial expansion, they claim. Driven by an emotional, non-rational desire to aggrandise itself. And pushing and pulling it all, as the New Statesman’s War of the Worlds-ish cover art suggests, is the mad, bad demon himself – Vladimir Putin.

Worse still, over the past few days, Western politicians have been grandstanding in response to the putative Russian threat. Foreign ministers of the G7 group of rich and entitled nations have said Russia faces ‘massive consequences’ if it does what it is supposedly itching to do and invades Ukraine. Germany is threatening to cancel the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. The US, in the words of secretary of state Antony Blinken, is ‘prepared to take the kinds of steps we have refrained from taking in the past’. And the UK, fronted by its tank-driving foreign secretary, Liz Truss, is promising to ‘consider all options’ in any potential retaliation against Russia.

This, it seems, is how Western politicos and pundits happily imagine the world, divided between the good, peace-seeking nations of the West, and the disruptive, chaos-inducing power of Russia – a power desperate to revive some quasi-Tsarist dream of Greater Russia.

This is a simple-minded Manichean take on geopolitics. And it wilfully obscures the West’s own role in stoking tensions in eastern Europe. For Russia is not really the main actor here, and certainly not the agent of chaos. Rather, what’s happening in and near Ukraine is a product of a long-running fear, on Russia’s part, of Western expansion. If there is a disruptive, destabilising force here, it is not the Kremlin, it is NATO.

From Russia’s perspective, it is NATO that has long been doing all the running here. From the mid-1990s onwards, NATO has been determinedly expanding eastwards, eating into Russia’s sphere of influence. In 1997, Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic signed up. Former Soviet satellites Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were admitted in 2004. In 2009, Croatia and Albania joined. And crucially, at NATO’s Bucharest summit in April 2008, NATO agreed that Georgia and Ukraine ‘will become members’, although it did not outline specific plans as to how and when this would happen.

This promise to incorporate Georgia and especially Ukraine into NATO was always going to appear as a threat to Russia. How could it not? Western powers, never shy of sounding off against the Red Menace, would effectively have extended their own sphere of influence right up to Russian borders. And so, as we saw with the 2014 annexation of Crimea, one of Russia’s principal geopolitical objectives has been to resist NATO’s expansion.

This is what is animating Russia’s current actions in relation to Ukraine. Not a desire to revive the Russian Bear or build a new empire. But a desire to protect itself and, in the case of Ukraine’s Donbas region, ethnic Russians living in Ukraine.

There is nothing irrational about Russian fears. For a start, in recent years, Russia has seen NATO indulge in its own military build-up in eastern Europe, situating multinational battlegroups in Baltic states, sending warships into the Black Sea and placing weaponry and engaging in large-scale military exercises in Poland. What’s more, NATO has consistently reiterated its plan to make Ukraine a NATO member. As recently as October, US defence secretary Lloyd Austin said during a visit to Europe that Ukraine and Georgia have an ‘open door to NATO’.

That is a provocation for Russia. A threat. As Mary Dejevsky has written on spiked, Russia is reacting to Western political and military manoeuvring on its border. It is in defensive, not offensive, mode. So there is every reason to think Russia’s foreign ministry was being entirely sincere when, in order to resolve the current crisis, it asked NATO to ‘officially disavow the decision of the 2008 Bucharest NATO summit that “Ukraine and Georgia will become NATO members”‘.

If there is to be a resolution of the conflict in and over Ukraine, the West first needs to acknowledge its own role in the crisis. And then perhaps it might be in a position to understand Russia, rather than just demonise it.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.