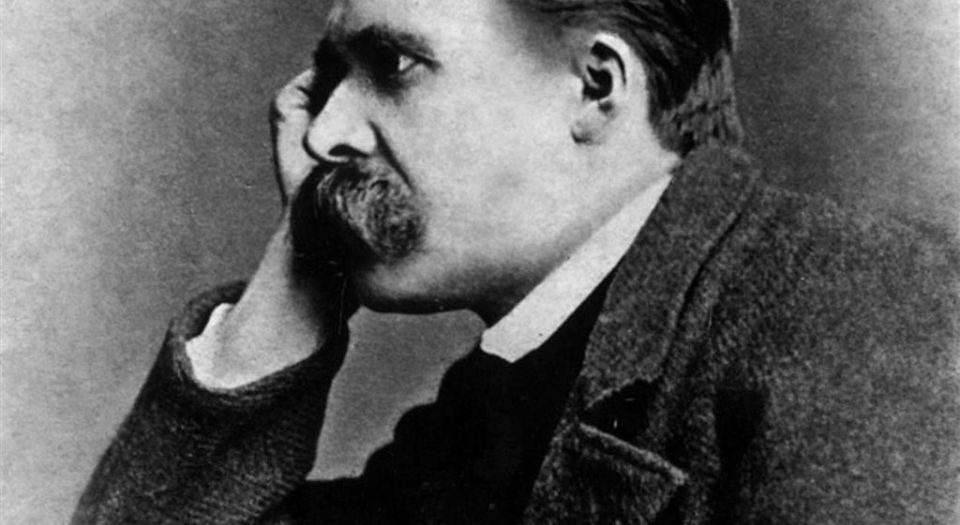

Banning Nietzsche: why it’s time to end No Platform

Instead of complaining about individual bans, students need to attack campus censorship at its root.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Last week, the news that University College London’s students’ union (UCLU) had, in March of this year, voted to ban a Nietzsche reading group rattled Twitter and the comment pages. Originally set up as ‘Tradition UCL’, the group had put up posters on campus promoting such philosophers as Alain de Benoist, Julius Evola and Martin Heidegger, and bearing slogans like ‘Equality is a false god’, and ‘Too much political correctness?’.

The group itself, which has failed so far to release a statement, seems, at worst, to be a pretty small and batty clique. A group so avowedly committed to ‘traditionalist art and philosophy’ may well not be the most popular society at the UCL freshers’ fair. Nevertheless, on the issue of political correctness, it may well have a point, given that UCLU promptly deemed the ‘Nietzsche Group’ very politically incorrect by voting to deny it any union funding or benefits for two years on the grounds the group was ‘promoting a far-right, fascist ideology at UCL’ which threatened the ‘safety of the UCL student body and UCLU members’.

News of the ban, which had largely gone unreported until spiked’s Free Speech Now! campaign brought it to light, was rightly met with contempt by various students, academics and onlookers. Indeed, UCLU’s actions seemed to undermine completely the entire purpose of a university. The study of problematic, even anti-human and far-right-leaning thinkers, especially those as seminal as Nietzsche or Heidegger, is essential to a rigorous academic environment. As one witty tweeter put it: ‘This is absurd. University is pretty much the only place where anyone reads Nietzsche.’

UCLU’s use of anti-fascist rhetoric to justify the ban made the move seem all the more unhinged. To equate the quashing of one wacky reading group with a grand fight against the far-right is tenuous at best. As has been noted recently on spiked, anti-fascism in the UK has become little more than political shadow play. In the absence of any meaningful left-wing consensus, anti-fascist groups are merely fluffing up the spectre of fascism in order to have a clear enemy to strike progressive poses at. UCLU officers, who have long had a reputation for being Eighties-esque mockney-Marxist throwbacks, seem to be completely divorced from reality when they claimed the ban was part of ‘a united front of students, workers, trade unions and the wider labour movement’. (With a measly 16.3 per cent turnout in the last union elections, the UCLU executive can barely claim ‘solidarity’ with UCL students, let alone some burgeoning workers’ movement.)

But even the most sympathetic observer would find it hard to justify UCLU’s handling of the Nietzsche Group debacle. Last Friday, UCLU released a statement defending its ban and putting it in the context of a 2013 policy, passed by the union, that gives it powers to ‘deny a platform’ to fascist organisations – namedropping the British National Party (BNP) and the English Defence League (EDL), despite the fact that both groups had, by 2013, effectively imploded. By raising the spectre of ‘No Platform’, UCLU showed itself to be even more cut off from its contemporaries. The No Platform policy, which was adopted by the National Union of Students (NUS) in 1974 and used by various anti-fascist groups over the past 30-or-more years, has been roundly discredited. While it remains on the NUS’s books, most UK universities have either overturned it or simply refused to enforce it. Even anti-fascist group Hope Not Hate announced that it had dropped the policy in 2013, with coordinator Nick Lowles saying that the policy was ‘ineffective’ and that Hope Not Hate would rather ‘be in the argument’ with the far-right.

However, while this particular ban seems to fly in the face of common sense, as well as popular opinion among student and anti-fascist activists, UCLU’s decision is hardly an aberration. Over recent years, student unions in the UK have attempted to ban everything from pro-life societies to supposedly ‘sexist’ materials, such as the Sun newspaper’s topless Page 3 feature. While No Platform may seem like a dusty relic, its underlying logic – that some ideas are too explosive to be aired and some students are too feeble-minded to challenge them in an open forum – has remained unchallenged. From No More Page 3 to No More Nietzsche, the legacy of No Platform lives on.

If anything, British student unions have become even more patronising of late. While No Platform policies were originally justified on the grounds that students might unthinkingly imbibe fascist ideas if they were exposed to them, the bans of today are argued for in the language of safety. The suggestion from UCLU that the Nietzsche society threatened the ‘safety of the UCL student body’ speaks to a trend in which ideas and words, in and of themselves, are seen to pose a direct danger to students, who student politicos assume will be so offended by a Nietzsche poster or a topless spread in the Sun that they’ll be reduced to a quivering wreck.

Rather than feigning surprise at UCLU’s petty affront to academic freedom, students must make a robust defence of free speech on campus. Bringing down No Platform, once and for all, would be a good place to start. Students need to denounce censorship, not only as ‘ineffective’, but as a fundamental affront to their ability to challenge ideas head on. What’s more, they must rush to the defence of anyone who feels the brunt of censorship, no matter how abhorrent their views may be. As Thomas Paine put it: ‘He that would make his own liberty secure must guard even his enemy from oppression; for if he violates this duty he establishes a precedent that will reach to himself.’ If students refuse to defend free speech for all, they can’t complain when the books start being burnt.

Tom Slater is assistant editor at spiked and coordinator of the ‘Down With Campus Censorship!’ campaign. Find out how you can get involved here.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.