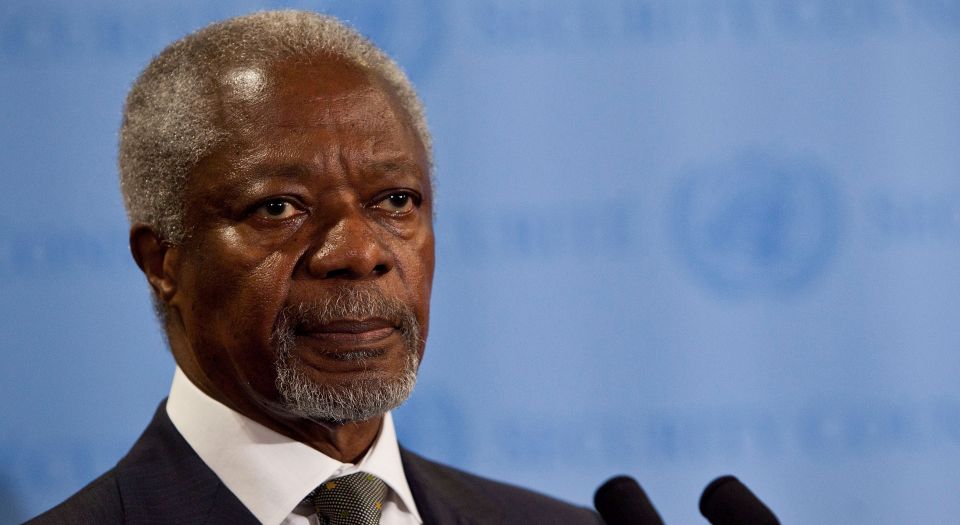

Kofi Annan: frontman for Western meddling

How the former UN chief gave cover to the West’s bloody wars.

Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary-general who died on Saturday aged 80, did not take the usual route to international statecraft. He was born in Ghana (then called the Gold Coast) in 1938 to an Ashanti aristocratic family. He was never elected as a political leader in his own country or any other. After graduating with an international relations further degree in Switzerland, he served in the World Health Organisation and later the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. He became secretary-general in 1997.

Annan’s long march through the institutions of the UN was respectable if unremarkable. But changes in the role of the UN after the collapse of the Soviet Union helped his prospects. When the Soviet Union was one of the permanent members of the UN Security Council, with a veto, it had been difficult for the leading Western powers to get their way. But after the USSR’s collapse, Russia was led by the abject American stooge Boris Yeltsin, and so America, along with Britain and France, started to get their way.

The dominant Western powers reacted to the end of the Cold War in two – contradictory – ways. On the one hand, they were much more confident about intervening in the developing world. On the other hand, they were much more cautious about acting unilaterally or explicitly in pursuit of their interests. The result was a new policy of ‘humanitarian intervention’. That meant more direct intervention, though it was intervention that was presented as being for the general good, in pursuit of humanitarian goals, and most definitely not selfish Western interests. Behind the scenes, of course, the main players were the Western powers, principally America, and, to a lesser extent, Britain, France and Germany.

At the United Nations, this new spirit of humanitarian intervention meant two things. First, interventions carried out by Western forces (with support from developing-world armies) took place under the official umbrella of UN operations. Second, UN officials from the developing world were more in demand as frontmen for these interventions, in order to package them as ‘humanitarian’ rather than Western.

The first non-Western UN secretary-general was not Annan, but his predecessor, the Egyptian Boutros Boutros-Ghali. Boutros-Ghali had been proposed by France, and he was often thought of as too close to French policy, meaning that he was, in a very modest way, cautious about wholeheartedly endorsing US goals. But US leaders were in no mood to brook any dissent. And Kofi Annan began his rise to the top.

The clash between Boutros-Ghali and the US came to a head when a UN operation was underway against the Serb leadership over Bosnia in 1996. America’s leaders wanted an all-out air attack on Serb ground positions in support of Bosnian secessionists. Boutros-Ghali balked and used his UN veto over NATO airstrikes. When Boutros-Ghali was in transit, however, Annan, who was by that time the under-secretary-general for peacekeeping, held the veto on the secretary-general’s behalf. Annan gave his support for NATO airstrikes against Serb positions. According to US diplomat Richard Holbrooke, at that moment Annan ‘became secretary-general in-waiting’. Boutros-Ghali alienated the US still further when he published a report on the deaths of 100 refugees in a UN camp after an Israeli attack.

Boutros-Ghali became the first secretary-general to be refused a second term of office. America’s assistant secretary of state for African affairs said that the US would support ‘any African for UN secretary-general as long as it wasn’t Boutros-Ghali’.

In office, Kofi Annan did not depart in any significant way from the US script. He supported the UN-backed air attacks and sanctions regime on Iraq. In 2003, when America could not get UN Security Council approval for the war against Iraq, Annan only objected to say that they ought to go ahead with UN approval – though he later suggested the war might have been illegal.

By the end of Annan’s term, the high watermark of UN humanitarian intervention had been passed. The failure of the post-war UN-backed government in Iraq undermined much of the certainty around humanitarian intervention, though it did not end it. Annan left office in 2006, with the UN’s status much diminished. His son Kojo had been accused of profiting from the Iraq oil-for-food scandal. And Kofi was later accused of having sat on reports detailing sexual harassment by Ruud Lubbers, then the UN high commissioner for refugees.

Those scandals, though, were not the real problem with Kofi Annan’s years at the UN. The real problem was the support he gave to those leading powers who were trying – and failing – to work out their own lack of purpose by remodelling the world.

James Heartfield is author of The Equal Opportunities Revolution, published by Repeater. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.