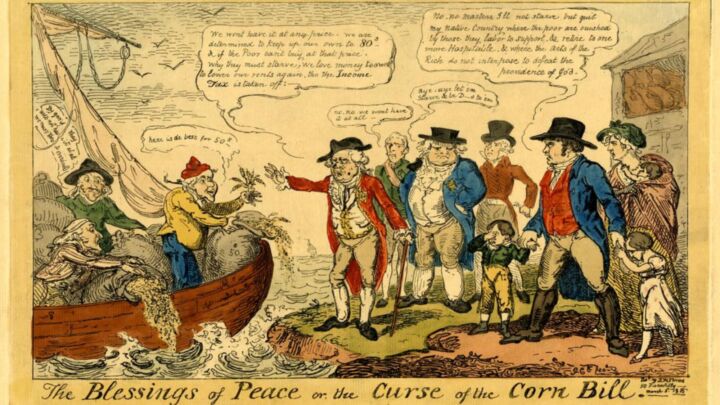

Australia’s new battlefield: insiders vs outsiders

As in Brexit Britain and Trump’s America, it’s the elite vs the people Down Under.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

If you trust the polls, Labor leader Bill Shorten will win next month’s Australian federal election, as surely as the British voted to remain in Europe and Hillary Clinton won the US presidency in 2016.

Shorten has been the consistent frontrunner for more than two years and faces a centre-right coalition with weakened authority after five years of internal division and two changes of leader.

Yet there is good reason to suspect that polling may be as reliable as it was in 2016.

Like Britain, the US and much of the democratic Western world, Australia is undergoing a transition from the politics of left and right to a contest between conformist insiders and woefully disobedient outsiders.

Shorten and the prime minister Scott Morrison feel obliged to tread cautiously across a treacherous cultural landscape. One false move could trip the next political explosion, as Shorten did two weeks ago when he announced a bold policy on electric vehicles.

Australia was lagging behind the rest of the world, he said. A Shorten government would ensure that by 2030, 50 per cent of vehicles sold on the market would be powered by batteries.

Had Shorten sought advice from anyone living more than five kilometres outside the Canberra political triangle, the thought bubble would never have been released.

Australians love their cars with the passionate intensity mid-America displays towards guns. The backlash was immediate. Alan Jones, the country’s most popular talkback radio host, declared that the issue would lose Shorten the election.

Shorten compounded his problems two days later when he was asked by a breakfast radio presenter how long the batteries took to charge. ‘Oh, it can take, umm … it depends on what your original charge is, but it can take, err, eight to 10 minutes depending on your charge’, Shorten ventured.

A more accurate answer would have been eight to 10 hours.

Few Australians would be embarrassed by Shorten’s accusation that they are behind the rest of the world in the quality of the exhaust emitted from their tailpipes. They live in a country of vast distances and rough terrain with the third-lowest fuel taxes in the developed world. Miles per hour still counts for more in the Australian car market than miles per gallon.

Others are welcome to drive Ford Fiestas, VW Golfs and Vauxhall Corsa, the three top-selling vehicles in Britain. But they’re a little squashy for four grown men even without their fishing rods.

Which is why Australians prefer the Toyota HiLux, Ford Territory and Mitsubishi Triton, the current top-selling vehicles, which emit almost twice the CO2 of the Fiesta but are far better suited for rounding up sheep in a wet paddock.

Few nations could rival Australia in its unsuitability for electric vehicles. The challenge of installing chargers at convenient intervals along Australia’s 7.6million kilometres of roads is hard enough. It is considerably more difficult than in the UK, for example, where there are 77 cars per square kilometre, compared to Australia’s 2.5.

Utility vehicles, or ‘utes’ in the local vernacular, SUVs and four-wheel-drives account for more than 60 per cent of the small vehicle market in Australia and their popularity is growing.

There is no electrical equivalent of these vehicles on the market. We’re told that the Hyundai Kona could be on sale by Christmas, but at $60,000 – $20,000 more than the petrol version – you can forget it.

The global mania driving the introduction of electric vehicles seems puzzling viewed through Australian eyes. If Norway chooses to spend billions of krone earned by selling oil on subsidies to bribe its citizens to drive electric cars, then let them. Unlike the Norwegians, Australians do not have 31 billion watts of hydro-generated electricity at their disposal.

Yet the technological obstacles and investment challenges are treated with little regard by the elite, where anxiety about the predicted effects of global warming are keenly felt. Support for electric cars, like enthusiasm for renewable energy, is strongest in well-to-do suburbs close the city, frequently close to the beach, where they drive cars the least and are soothed by maritime breezes on stinking-hot summer days.

The hostility to electric vehicles is not helped by the performance of the political and policy elites who have a track record of policy disasters in energy. The last Labor government used draconian cross-subsidies to force investment in wind and solar power with unfortunate results.

Australians once enjoyed among the cheapest electricity in the world. Now it vies to be the most expensive. The intermittent supply from renewable energy has made the grid unstable. There have been lengthy blackouts in South Australia and Victoria, where coal-fired power stations have been forced out of the market.

The intellectual elites who created this mess still struggle to see where they went wrong. If it worked for Denmark, why wouldn’t it work here?

But Australia is a very different country. Like other net exporters of energy, the relatively high level of emissions per-capita does not reflect local habits.

It exports some of the world’s cleanest coal, thus contributing to a reduction of emissions in some countries. And if coal is considered too dirty, there’s always gas, in which Australia leads the world in exports.

Agriculture, of which Australia is also a net exporter, contributes 16 per cent to national emissions, most of which comes from enteric fermentation in ruminant livestock – a polite way of saying belching and farting, for which there is no known antidote.

These peculiar national characteristics help to explain why climate policy is Australia’s Brexit: the issue that divides the intellectual elites with their grand theories from the rest of Australia with its no-nonsense practical outlook. It is the touchstone issue on which the nation divides along non-party lines, and could once break up a barbie in those innocent days when the two tribes grilled their steaks together and parked their six-cylinder Holdens in the same drive.

Like Brexit, leaders would prefer if they didn’t have to take sides, for fear of causing offence and disunity within their own party. Like Brexit, however, there is no fence to sit on. Shorten, the leader of the party that pays increasingly little attention to the workers that once defined it, is siding with the intellectuals, promising to abate roughly three times the amount of greenhouse gas by 2030 than Australia is obliged to do under the Paris Commitment.

If he thinks such virtue-seeking will go unquestioned by hoi polloi beyond the beltway, he will be disappointed. It is proving to be an electoral disadvantage in the outer suburbs and in regional Australia where a Trump-like revolt, if it ever happened in Australia, would be likely to break out.

It is here that Morrison is discovering surprise middle ground on the continuous issue of climate policy. Like Shorten, he promises action to reduce emissions, which 70 per cent of Australians favour. His appeal, however, is toward practical, measured policy, rather than one that seems intellectually pure.

‘You don’t have to choose between the economy and the environment’, Morrison says. ‘You don’t have to choose between your job and the environment.’

Any predictions about the result next month must be heavily qualified. The political duopoly that has been in place since the end of the Second World War is fraying. Populist independents and pop-up parties are strengthening and will almost certainly hold the balance of power in the next parliament, as they have for the past 12 years. They may also increase their presence in the lower house, increasing the chances of a hung parliament.

The Liberal/National Coalition, which has been in government for 18 of the past 24 years, comes to the poll as a weakened force, despite an exceptionally strong economy and low unemployment. PM Scott Morrison, who has been in office for less than eight months, has gone some way to restoring the government’s fortunes and repair the internal disunity, but time was never on his side.

The weekend polls still put Labor ahead by 52 per cent to 48 per cent. Yet if Morrison can manage to tap the well of discontent against the outlandish climate policy pursued by much of the political class, the coalition may yet confound those who have written them off.

Nick Cater is executive director of the Menzies Research Centre and a columnist for the Australian.

Picture by: Getty.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.