Sanitising Bob Dylan

A Complete Unknown obscures the tumult of the Sixties and the radical politics of the folk scene.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

There are a lot of misconceptions and myths about the Sixties. James Mangold’s new Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, has a tendency to reinforce them.

The film recounts Bob Dylan’s early career, covering the period from his arrival in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1961 to his appearance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island, when he ostensibly transformed the folk-music scene with his electric guitar performance. While this biopic has undeniable strengths, those seeking to better understand the enigmatic Dylan, and the decade with which he will forever be associated, will be left disappointed.

Like most films and books about the Sixties, A Complete Unknown is guilty of portraying the era with a gauzy, romantic nostalgia. This contrasts with the growing library of less charitable stories of the era, generally written by younger members of the post-Boomer generations. They depict a smoke-filled, dystopic Mad Men decade, rife with sexism and racism.

To understand the Sixties, we should resist both these facile generalisations. The changes in America were more rapid-fire than in any other decade of the 20th century. Events occurred quickly in sequence – it was only 11 weeks from President John F Kennedy’s assassination to The Beatles’ first live appearance on American television, watched by over 70million. The assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King occurred within nine weeks of each other in 1968. That same year, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and the fateful Democratic National Convention happened in the same week. The Moon landing was the day after the ‘Chappaquiddick incident’, in which a young woman drowned after a car driven by Ted Kennedy plunged into a tidal channel. No single interpretation of the Sixties can capture such a tumultuous decade.

Considering the brief interval covered in A Complete Unknown, one of its shortcomings is failing to account for how rapidly societal changes occurred and how America morphed so much in just five years. Younger moviegoers may not realise, and older ones may have forgotten, that 1965 was in many ways quite different from 1961 – probably more different than 2025 is from 1991.

Without question, the strength of the film lies in the wonderful performances. Timothée Chalamet and Monica Barbaro are excellent in their respective roles as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Most of the rest of the cast are no less praiseworthy, although Elle Fanning as Sylvie Russo – a fictional character based on Dylan’s real-life muse, Suze Rotolo – is trapped in a cliché-ridden part. The movie’s best performance comes from Ed Norton as Pete Seeger, and he is deservedly in line for an Academy Award nomination.

Along with the acting, the music is brilliant with Chalamet, Barbaro and Norton doing their own singing. They have done their homework. Each sings enough like his or her

character to convey the brilliance of the originals, but not so much as to invite any invidious comparisons.

The movie’s plot and character development are thin, however, barely enough to keep the viewer involved. The story of the genius naif who comes to the big city to find success, and is overwhelmed when he does, would be unremarkable without the fine performances and music. A Complete Unknown is essentially a concert movie that doubles as a period piece, and doesn’t completely succeed as either.

The inevitable minor factual mistakes that occur in any movie are barely worth caviling over. Take the cry of ‘Judas’ when Dylan first plays his electric guitar. It didn’t occur at Newport in 1965, as the film suggests, but in Manchester in 1966.

One inaccuracy worthy of criticism is the portrayal of the Greenwich Village-era Bob Dylan. He had as many enemies as friends, some out of jealousy, some because of his abrasive personality. In A Complete Unknown, Monica Barbaro’s Baez calls him an ‘asshole’ to send a message to the audience that the young Dylan is not a nice guy. But if later accounts by the real Joan Baez, Suze Rotolo and Dylan’s first wife, Sara, can be believed, his personality was far more malignant than that portrayed in the movie. To his credit, he seems to have mellowed somewhat in later life.

An even more substantive objection is the consensus reinforced by the film that Dylan was the person who delivered folk music into the rock era and created the genre of folk-rock when he went electric at Newport. In truth, the real groundbreaker was Roger McGuinn, a taciturn, young Chicago guitar prodigy. As a youth he studied folk guitar and banjo, and by the time he was 20, he was backing for some of the country’s top folk groups. After spending time in Greenwich Village, he moved to Los Angeles to join the emerging rock scene. One day in 1964, he and his mates went to see The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night. Afterward, they formed a rock group, the Byrds, and McGuinn began experimenting with the 12-string Rickenbacker, the instrument George Harrison introduced.

Several months later, Dylan released an acoustic folk version of his song ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ on an album. McGuinn adapted it to the 12-string, altered the timing to give it a Beatle backbeat with a distinctive jingle-jangle melody, and turned to his Catholic roots, borrowing a melody from Bach for a distinctive intro. It was a unique sound, completely new on radio, and in April 1965, three months before Newport, the Byrds’ version of ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ became the top single in the US and UK. It was the first Dylan tune to reach No1. This was the birth of electric folk-rock and Dylan took note, even if the visionary McGuinn received little credit then and none in this film.

Jonathan Swift said that ‘It is the folly of too many to mistake the echo of a London coffee-house for the voice of a kingdom’. A Complete Unknown is guilty of mistaking the echo of a Greenwich Village for the voice of America. The movie is grounded in New York, with all the scenes taking place in New York City, New Jersey or Newport – all places where folk music was more popular in 1961 than it was in the rest of the US. Folk music would soon become popular nationally, but the movie fails to tell how evanescent that prominence was.

Shortly after the Second World War, folk music had been briefly ascendant. This was primarily due to the Weavers, a group that included Pete Seeger and Lee Hays, both of whom sang with Woody Guthrie in the 1940s. The Weavers’ recording of Lead Belly’s ‘Good Night, Irene’ in 1950 became the first folk song to reach No1 in the pop-music charts. Soon thereafter, when the group fell afoul of the House Committee on Un-American Activities for its Communist associations, folk music fell into obsolescence until the late Fifties and early Sixties. This was the Greenwich Village revival, where A Complete Unknown comes in.

Key to the resurgence of folk music was its association with the civil-rights movement. This association developed from 1957, when a handful of black kids were integrated into Little Rock Central High School, to 1963 and the March on Washington, when 250,000 joined together to call for economic and political rights for African Americans.

Even so, despite the efforts of John Hammond, Alan Lomax and others, the early Sixties folk-music craze remained confined primarily to the East Coast, several urban centres and college campuses. It failed to register much in the heartland of the country. Bob Dylan may have been drawing crowds in Greenwich Village cafés in 1962, but Elvis was still the most popular artist nationally. The rest of the country was doing the Twist with Chubby Checker, catching on to surf music from the West Coast, listening to R&B from Motown in Detroit and the emerging country sound from Nashville. The scene in A Complete Unknown where people are snapping up Joan Baez albums could likely only have happened in New York. Before 1965, she never had a Top 10 album nationally nor a single that reached higher than No50. Likewise, before 1965, Dylan never had a Top 10 album, nor a Top 30 single.

Baez became a household name when she appeared on the cover of Time magazine in November 1962, and Dylan did around the time of the March on Washington in August 1963. By then the popularity of folk music had peaked. It was not made for radio listening and could not compete with the other genres that radio stations were anxious to play. By the time of the JFK assassination in November 1963, folk-music popularity was gradually beginning to decline, with only Baez and a few others such as Peter, Paul and Mary straddling folk and pop. (The 2003 Christopher Guest mockumentary, A Mighty Wind, tells the story of the folk-music craze in a funny, yet sympathetic way.)

In A Complete Unknown, when Pete Seeger implores Dylan to save the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Seeger was either deluding himself or unaware that ‘pure’ folk music was on its deathbed in the US. Those diehards at the 1965 festival hoping for Dylan to remain acoustic were like the 19th-century stagecoach drivers ignoring the sound of the train whistle in the distance. Dylan heard the new sound, realised what it meant and moved forward. Seeger moved on to Vietnam War protest music. By 1969, the Newport Folk Festival had closed. It wasn’t revived until the 1980s at a smaller venue, and by then it was more country-music oriented.

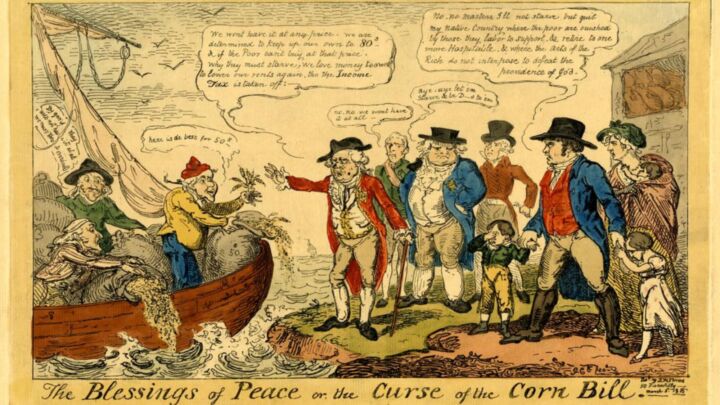

The other notable omission in the movie is the left-wing politics of folk music, which although essential to the art, is routinely ignored in contemporary recounts. Communism in various shades was bubbling just under the surface, and the Soviet Union saw the folk community as a conduit to infiltrating American society. Woody Guthrie was not a card-carrier but he aligned himself with the Communist front. His guitar was famously inscribed, ‘This machine kills fascists’. After the familiar first verse, later verses of Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land’ criticising private property are rarely played. School children don’t know that Guthrie wrote the song as an answer to Irving Berlin’s ‘God Bless America’, which he hated. (Ironically, Berlin grew up much poorer than Guthrie and, unlike him, celebrated the American dream.)

Of the aforementioned Weavers, Pete Seeger was a card-carrying Communist, who defended Joseph Stalin for many years. Other figures in A Complete Unknown who embraced some form of left-wing politics included John Hammond, Alan Lomax, Dave van Ronk, Joan Baez, Suze Rotolo and several artists not featured in the movie. Left-wing politics was part of the natural order when singing folk songs about unions, civil rights and injustice. And this is where Bob Dylan and the folk community diverged.

Dylan kept his politics out of sight, and only rarely did he let down his guard. Three weeks after JFK was assassinated, Dylan expressed sympathy for the pro-Soviet Lee Harvey Oswald at an awards dinner (he has since revised his songs and attitude about the assassination).

He pulled out of a highly anticipated television performance on The Ed Sullivan Show when he was not permitted to sing his song ‘Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues’ (the John Birch Society was a radical right-wing organisation). The publicity around not performing may have benefited his career more than had he performed.

It became a sticking point with the folk crowd that Dylan essentially refused to let them dictate his performances and politics. Left unexplored in the movie, this may have been the real reason for the schism between him and Pete Seeger rather than Dylan ‘going electric’. Later in life, Joan Baez conceded that she ‘wanted him to be a political spokesperson… to be on our team’. A major point of contention with him, she said, was that his ‘active commitment to social change was limited to songwriting’, rather than protest marches or public pronouncements.

Dave Van Ronk, briefly featured as an eminence grise in the movie, put it best when he said that, ‘We thought of him as hopelessly politically naive – but in retrospect he might have been more sophisticated than we were’.

Dylan didn’t want his guitar inscribed with any message. In his inimitable fashion, he told an interviewer in 1997:

‘’I’m not politically inclined… my talent isn’t in that area; it’s just to play music… I don’t care one bit about the Sixties… I know it was a time of great upheaval in the world, but still I don’t care about them… I didn’t grow up in the Sixties, so “Bob Dylan the Sixties protest singer” isn’t me at all.’

Vintage Dylan misdirection.

A Complete Unknown takes similar liberties with the man and the folk movement. But based on the music and performances, the movie is worth seeing, if not totally believing.

Cory Franklin’s The Covid Diaries 2020-2024: Anatomy of a Contagion As It Happened, is now available on Amazon in Kindle and book form.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.