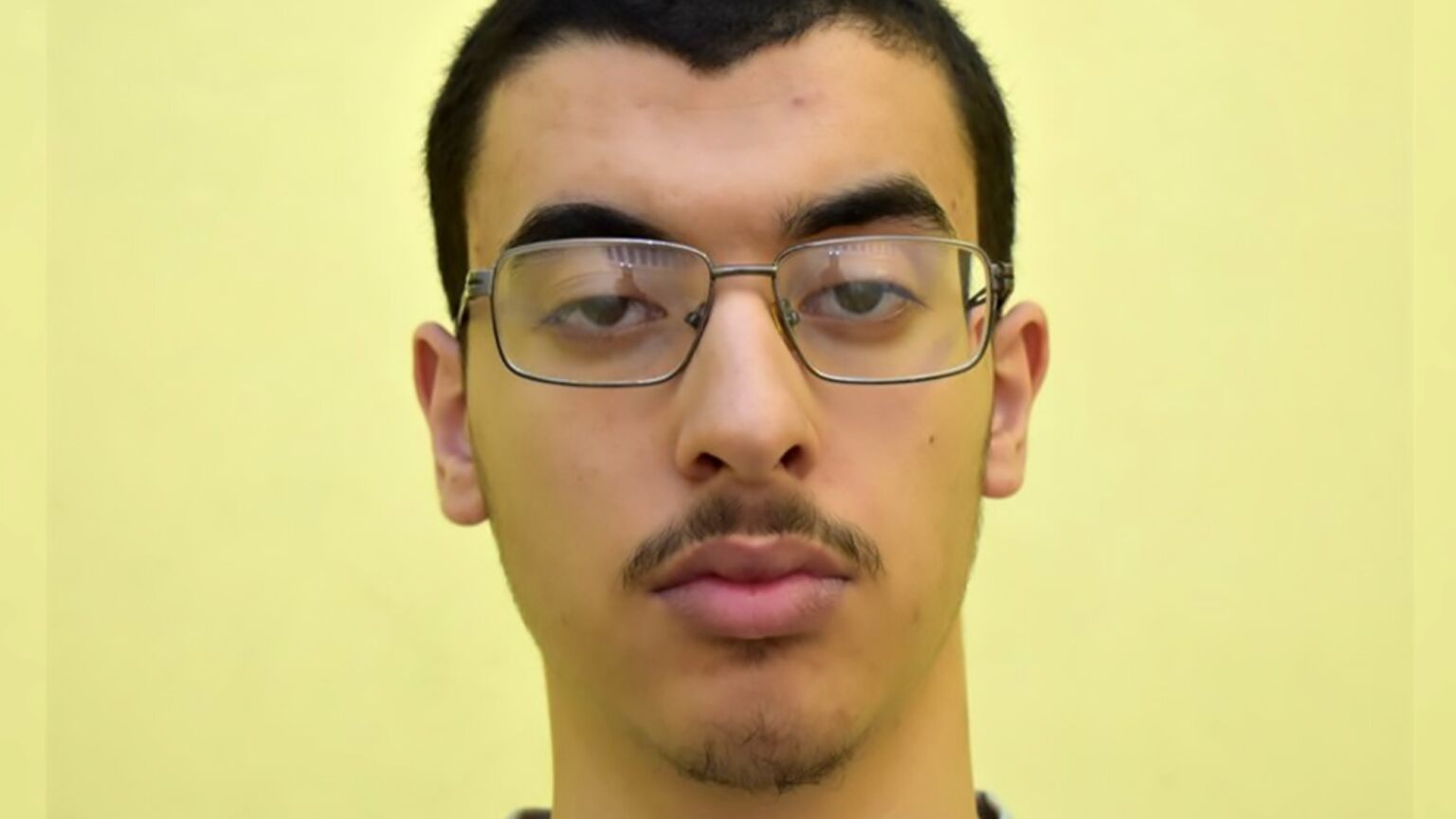

How the British state enabled the Abedis

Manchester Arena terrorist Hashem Abedi’s rampage in prison is only the latest in a long line of failures.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It’s no secret that Hashem Abedi is a violent, murderous Islamist. The 28-year-old was sentenced to life in prison, with a minimum term of 55 years, in 2020, for helping his brother, Salman Abedi, carry out the horrific Manchester Arena bombing in 2017. A few months after being incarcerated, Hashem, alongside two other prisoners, then engaged in what a judge described as a ‘vicious’, premeditated attack on a prison officer. There was little doubt that they would have killed him if they’d been able to.

This is why the news that Abedi was able to attack several other prison officers at HMP Frankland on Saturday, stabbing them with ‘homemade’ weapons and throwing hot cooking oil over them, is so disturbing. After all, HMP Frankland is a high-security, category A prison. It is used to house some of the most dangerous individuals in the UK. The fact that a known, violent, high-profile killer was able to manufacture his own weapons and gain access to scalding cooking oil, in what ought to be one of the most surveilled places in the British Isles, beggars belief.

Abedi’s attack, which has put three officers in hospital with what were swiftly reported to be ‘life-threatening injuries’, is an indictment of our prisons. It points to a carceral system that is seemingly unable to deal with the Islamist threat posed from within.

No doubt, part of the problem is the sheer lack of resources. Over the past three decades, the prison population in England and Wales has doubled, while the number of frontline prison staff has fallen. This is a recipe for disaster. Danger signs will be missed and illicit activity will bloom out of wardens’ sights.

But there is also a big problem with Islamist terrorists within prisons in particular. A combination of institutional complacency, incompetence and a lack of resources has allowed Islamist gangs to flourish within the prison estate. This has led to a rise in attacks on officers and inmates. In 2022, Jonathan Hall KC produced a damning report in which he warned of the emergence of groups of prisoners whose ‘Islamist stance… condones or encourages violence towards non-Muslim prisoners, prison officers and the general public’.

By all accounts, HMP Frankland is a grim case in point. In the weeks leading up to Abedi’s attack, it was reported that the prison had been overrun by Islamist gangs, and that inmates who refused to convert were being forced into separation units for their own protection. HMP Frankland’s managers denied the claims. But this attack certainly suggests that staff are losing control to jihadi inmates.

This failure to deal with the Islamist menace is not confined to the prison system, of course. Indeed, Salman and Hashem Abedi were enabled by one catastrophic failure of British officialdom after another.

Arguably, they should never have ended up in the UK in the first place. Their father, Ramadan, was a committed Islamist – a member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, a bitter opponent of Colonel Gaddafi. Yet he and his wife, Samia, were granted asylum in the UK in the 1990s, supposedly fearing persecution back in Libya. They settled in Fallowfield, south Manchester, where their children were born in the mid-1990s.

The Abedis returned to Libya in 2011 to fight in the civil war – having apparently gotten over their fear of returning. In 2012, Salman and Hashem (and their older brother, Ismail) came back to Manchester without their parents. They clearly held violent Islamist views by this point, which was hardly surprising given they’d spent some of their formative years with Islamist militias. There were reports from their local mosque about Salman’s veneration of suicide bombings and, later, his tacit support for ISIS.

In the autumn of 2012, Salman was reprimanded by his college for disrespectful attitudes towards women. Later that year, he physically assaulted a female student after a row over the length of her skirt. If that flag wasn’t red enough for the authorities, Salman headed back to fight in Libya again in 2014.

But no alarms sounded. On countless occasions, the Abedi brothers were treated with a remarkable complacency by the authorities. In 2016, Salman was even able to phone and meet another British Libyan Islamist, Abdalraouf Abdallah, who was then serving time in prison for terror offences. Abdallah, described as a recruiter for ISIS, played a key role in ‘radicalising’ Salman and Hashem ahead of the Manchester Arena bombing, where Salman blew himself up and took 22 souls with him. Abdallah was himself released from prison last year.

The British state’s almost wilful disregard of the threat posed by the Abedis is indicative of its broader complacency towards the Islamist threat in general. The brothers’ jihadist hatred was allowed to fester in plain sight. They travelled back and forth from a warzone unmolested. They fraternised with Islamist extremists, in Britain and in Libya. How were they ever allowed to get anywhere close to the Manchester Arena that awful night?

In 2023, the head of MI5 issued a public apology for missing opportunities to prevent the bombing. But after Hashem’s violent assault on prison officers on Saturday, there is little to suggest the state has learnt any lessons. Just as it failed to protect the 22 children, young people and parents slain at that Ariana Grande concert eight years ago, it is failing to protect prison staff today.

The Abedis bear full responsibility for the horrors they have inflicted on ordinary people. But the useless British state made it far too easy for them.

Tim Black is associate editor of spiked.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.